HIERARCHY AND HERD LIFE - WHAT WE LEARN FROM OBSERVING HORSES IN FREEDOM

Horses live in highly social groups with subtle, structured interactions. Observing free-living herds reveals their natural hierarchy, based on non-verbal communication, mutual trust, and peaceful leadership.

Horses are profoundly social animals. Long before they were ridden, trained, or confined to stalls, they evolved in structured groups where every individual had a role. Observing horses in freedom, in large paddocks, reserves, or sanctuaries , allows us to rediscover this essential dimension of their nature: herd life.

Far from common misconceptions about so-called "dominance", equine hierarchy is based on subtle mechanisms that are often misunderstood. Better understanding them means improving horses’ well-being — and building a fairer relationship with them.

The Horse: A Naturally Gregarious Animal

Horses are gregarious animals, meaning they naturally live in groups. This social organization is primarily a matter of survival: a lone horse is an easy prey. Within the herd, members take turns watching for danger, move together, eat, and rest close to one another.

This need for cohesion is so deep that even a domesticated horse kept alone can develop stress, stereotypic behaviors (such as cribbing or weaving), or behavioral depression.

A Subtle Hierarchy, Far from Dominance Theories

Contrary to some outdated approaches based on dominance, horse hierarchy is neither rigid nor violent. It relies on:

-Experience (often that of the older mares),

-The ability to anticipate danger,

-Emotional stability.

It is not about brute dominance, but rather situational leadership: one horse may lead the herd to water, while another helps defuse internal tension. The hierarchy is flexible, adaptive, and oriented toward the well-being of the group.

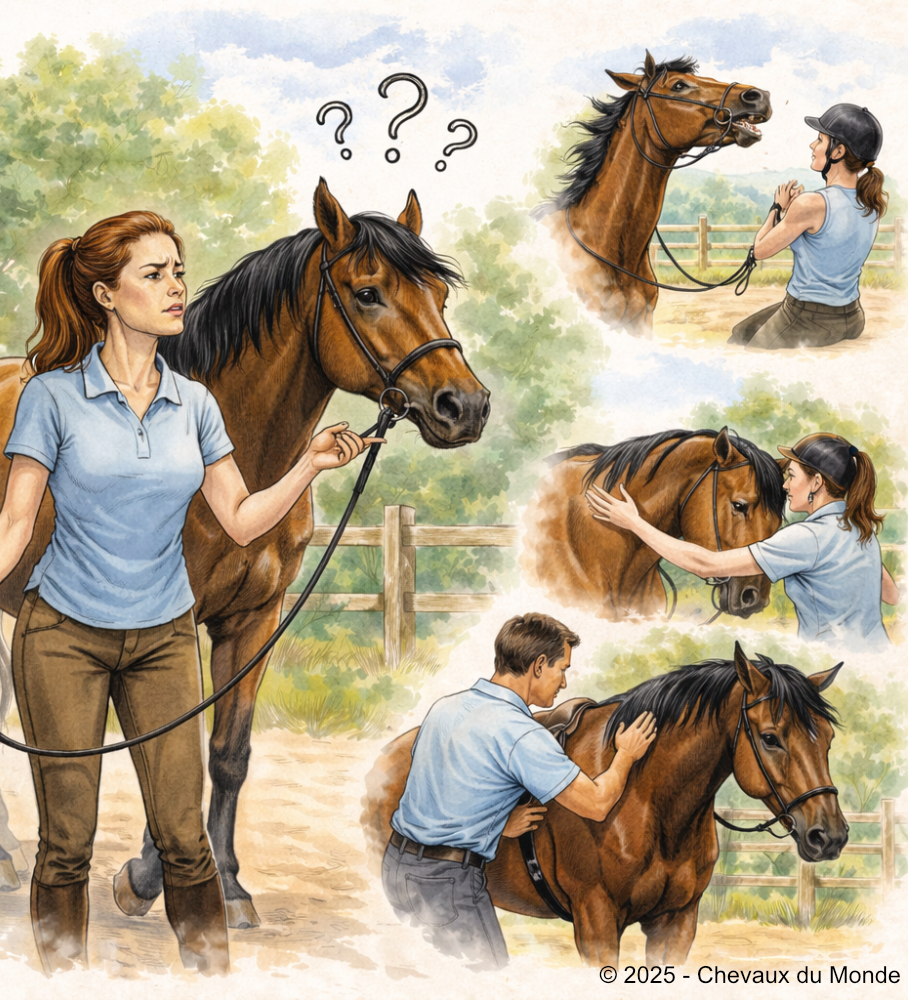

Communication: The Foundation of Cohesion

Horses communicate primarily through body language: ear position, lip tension, neck movement, gaze, lateral displacement…

Examples include:

-A horse pinning its ears is not always aggressive — it may simply be signaling discomfort.

-A movement toward another horse without contact may be enough to ask it to move.

-Mutual grooming (often at the withers) is a calming ritual that strengthens social bonds.

Young horses engage in frequent play, which helps them learn the social codes of the herd, boundaries, and self-control.

Equine Friendships and Collective Well-Being

Hierarchy isn’t everything. Horses also form lasting bonds: they choose companions to rest with, play with, or move with.

These friendships can even cross species — some horses bond with donkeys, ponies, or other animals.

Forced isolation is a form of suffering. Conversely, a socially enriched environment (companions, freedom of movement) promotes better psychological and emotional balance.

What Humans Can Learn from This

Understanding hierarchy and herd life leads us to rethink certain practices:

-The need for control gives way to trust-based relationships.

-We favor suggestion over imposition.

-We learn to read subtle signals (tension, discomfort, invitation) instead of forcing a response.

It also invites us to improve the environment we offer to horses:

-Life at pasture or in collective paddocks,

-Access to companions,

-Respect for natural rhythms.

Observing horses in freedom means rediscovering a world of nuance, patience, and mutual respect. Every interaction is a product of subtle body language and a delicate balance between the individual and the group.

It is up to us, humans, to listen and learn. By respecting the natural dynamics of the herd, we build more peaceful, lasting, and respectful relationships with the horse.

Sources :

Martine Hausberger - Des soupirs qui interpellent

Sue M. McDonnell - The Equid Ethogram: A Practical Field Guide to Horse Behavior